An interesting story has been unfolding over the past few weeks in the world of Magic: The Gathering. Its cast, and their actions, are giving us a valuable look at how you can create a better user experience without fundamentally changing your product’s user interface. They’re showing us the value of being aware of your user’s context, and how your product can be reshaped when that context changes. And, they’re highlighting how you can strengthen your brand through making a better experience for your users.

Magic: The Gathering is a collectible card game introduced by Wizards of the Coast in 1993. In Magic, players cast spells using cards in an attempt to influence the game. Each player starts at 20 “life,” and tries to use a combination of cards and effects to drop their opponent’s life total down to zero.

Players combine cards from their own collection to create decks that they can use to play against each other. These decks can be built to fit into one of many different formats — a way of playing the game — which are defined by the range of cards that players are allowed to use.

Wizards of the Coast releases new sets of cards twice a year, which go directly into a format called Standard, which limits its card pool to those that were released over roughly the past two years. Another format, Legacy, allows almost every card ever printed in Magic’s 23-year history.

Since the cards used in Magic are collectible—with some cards being more useful in player’s decks than others—there’s a thriving secondary marketplace where players can buy and sell individual cards through local brick-and-mortar shops or online vendors.

TCGPlayer.com is one of these online marketplaces. It’s a platform for both players and card sellers: much like eBay, it creates a common storefront where players can buy cards from any number of independent shops. If your business sells Magic cards in North America, it probably has a presence on TCGPlayer.

Our story begins with an individual named Craig Berry. As a player and a “speculator”—more on this later—Berry saw an opportunity that he could take advantage of and initiated what’s called a buyout. In just one day, he bought every copy of card called “Moat” that he could find on TCGPlayer and eBay.

With almost no copies of Moat left to be found online, Berry — and other vendors — would be free to re-list the card at any price they liked.

The Magic community was outraged.

“My personal view? This type of shit is fucking disgusting …” — MLorent

“Is the secondary market becoming toxic?’ I would say yeah, a while ago.” — jsmith218

To understand this buyout — and the community’s reaction — we need to take a look at the game’s history.

When Magic: The Gathering was released, it wasn’t designed as a collectible card game. The idea of a secondary market where players could buy and sell game pieces was unheard of. Print runs were limited, and before long, supply lagged far behind player demand. Boxes and packs vanished from store shelves for double or triple the MRSP while individual cards skyrocketed in value.

In the game’s infancy, Wizards of the Coast didn’t have a strong handle on how to manage a collectible card game. In late 1995, the company released a huge print run of the latest set — Chronicles — which consisted of nothing but reprints. This huge supply of reprinted cards flooded the collector market. Prices plummeted. Collectors felt betrayed — and the future of the game was at risk.

In response, Wizards announced the Reserve List. Cards on the Reserve List would never be reprinted. Through the Reserve List, collectors could hold faith in the value of their collections: they cards they owned would be safe from reprinting in the future.

The Reserve List included a card called “Moat.” Moat is a staple in the Legacy format: if you want to play one of many popular decks in Legacy, you need to own Moat.

And suddenly, Craig Berry owned almost every copy of Moat available online.

Though many of the players expressing their outrage over the buyout had no intention of buying copies of Moat for themselves, they were upset at what they saw as manipulation of card prices and the implications on the long-term health of the Legacy format.

How could Legacy survive as a format if a single person was able to control the supply and price of a card that many new players needed in order to start playing? And who’s to say that he wouldn’t do it again — or worse, that others would join in and start to do the same? (In fact, Berry did just this. Another staple of the Legacy format, “Lion’s Eye Diamond,” was bought out just a day later.)

“Burn the reserved list. This kind of price gouging and market manipulation will eventually kill eternal formats, making these cards worthless.” —mtgfinancereform

The community called for Wizards of the Coast to abolish the Reserve List. They asked sellers to take responsibility in preventing buyouts. But these weren’t realistic paths: for Wizards of the Coast, to abolish the Reserve List would be to once again betray the trust of long-time collectors (not to mention open them up to a class-action lawsuit). For platforms like TCGPlayer, to prevent buyouts would be to actively harm their own profitability and relationship with sellers.

Though TCGPlayer held no responsibility for the buyout — their platform was simply the venue through which the buyout occurred — they stepped up.

They recognized that a large part of Craig Berry’s power — and other speculators like him — was held in a number on their platform: the TCG Mid.

As an online marketplace, TCGPlayer’s platform listed the low, median, and high price for each card they listed. These values reflected the prices that sellers set on their own stock, which was then sold through TCGPlayer’s platform. In addition to this easy-to-access data on their own platform, they made the data available to developers to use in their own applications through an API, which resulting in widespread adoption of the “TCGPlayer Median,” or “TCG Mid,” among players and sellers to value cards in their collections.

Unfortunately, this value could be manipulated. So long as Craig Berry owned all copies of a card, the supply was severely limited.

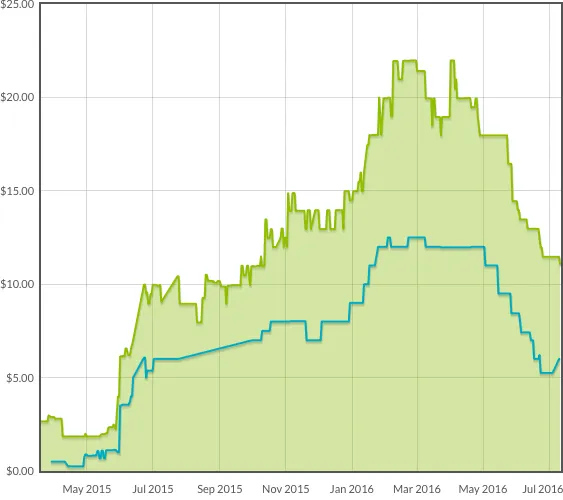

Card values naturally rise and fall over time in response to a number of factors, such as their perceived effectiveness in player’s decks. Take, for example, this price chart for a recently-released card, “Kolaghan’s Command,” whose value has steadily risen and fallen:

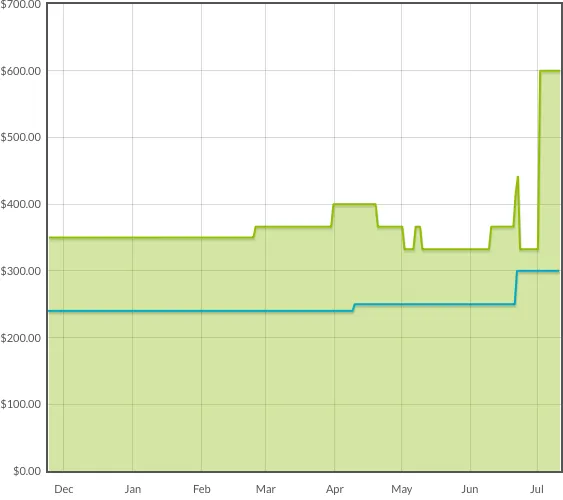

Buyouts, on the other hand, result in a sudden and dramatic price increase, like what we see in the aftermath of the Moat buyout:

Buyouts like these are an ongoing problem in Magic’s secondary market. They’re often driven by speculators — individuals who believe that a card’s value is certain to rise, and in wanting to get in early by buying many copies of the card while its value is low, inherently cause prices to rise in response to limited supply. Since these values are tied to the price at which sellers are listing their cards, a buyout is an effective way to dramatically increase the value of a card and profit off of the difference.

“There's a very clear reason, and it has to do with how TCG Player lists prices. After buyout, only one vendor had copies at $50.” —Joe Rincione on Twitter

In an announcement on the TCGPlayer website late last week, Chedy Hampson, TCGPlayer’s CEO, shared details about how TCGPlayer is rolling out a long-planned change in how pricing data is shown.

Instead of averaging the price of cards for sale — the TCG Mid — they’re now averaging the price paid in completed sales — the “Market Price.”

When Berry bought out Moat, the TCG Mid price jumped from $375 to $654. This doesn’t necessarily reflect the true value of the card: while it might be listed for $654, it might not be selling for $654.

With the introduction of the new Market Price value, the true value of Moat on TCGPlayer became $354: the average price that users actually paid for the card, rather than what sellers wanted to receive for the card.

In addition, the company is adding a new data point, called “Buylist Market Price.” When players want to sell their cards to a seller, they expect to receive less than the actual value of the card — after all, the seller has to make a margin on the card’s eventual sale. The price that the seller is willing to pay for a card is known as the “buylist price.” Even after Moat’s value spiked to $654, sellers weren’t willing to pay more than $290 for the card.

The new Buylist Market Price averages out how much sellers are willing to pay players for a card, which, together with the Market Price, gives a much more accurate reflection of a card’s real-world value.

The Magic community is responding very well to these changes, as evidenced by numerous glowing comments across social media channels like Reddit and Twitter.

“I’ve mentioned this elsewhere, but just wanted to say a big THANK YOU again for responding to this issue so quickly. I look forward to buying and selling on TCGPlayer for years to come.” —Reddit user urza_insane

While TCGPlayer’s actions aren’t a silver bullet for stopping buyouts—as long as card availability is restricted, they will continue to exist, and indeed, are still underway—their actions will still have a real, positive impact on players’ and sellers’ abilities to value their cards in a way that doesn’t affect TCGPlayer’s business model or its relationship with buyers or sellers.

This is a fascinating story from an UX perspective.

For starters, it illustrates how much impact you can have on your product’s user experience without fundamentally changing your product’s user interface.

The change from “TCGPlayer Mid” to “Market Price” is one that will have a massive, positive impact on the user experience for almost all of TCGPlayer’s users (except those trying to initiate buyouts). It takes the power of “price” out of the hands of sellers and speculators, and gives it to users. Before, if a seller wanted to say a card cost $654, players had no defence: TCG Mid agreed with the seller’s valuation. Now, players can look at the Market Price, and say “No; this card is worth $354.”

However, the changes to the platform’s UI are minimal. At its core, it’s a number: a value that’s changing from one amount to another.

The story also illustrates the value of being aware of your user’s context — and how changes to that context can shape your product over time.

TCGPlayer doesn’t exist in isolation. It’s not simply a platform that lets players buy and sell cards. Each of TCGPlayer’s users are operating in their own context, which includes their past experiences, their knowledge, and their emotions. This context influences their experience on TCGPlayer, even if TCGPlayer itself isn’t responsible.

When Berry bought out Moat, he shifted the context in which TCGPlayer’s users were operating. It was now being affected by the existence of the Reserve List, the implications that the buyout had on the long-term health of the Legacy format — and by extension, “their game” — and a passionate community outcry.

That TCGPlayer were working on the new Market Price and Buylist Market Price features for some time shows that they were in tune with their user’s context, and understood how their product could draw from that context to shape a better experience. Buyouts weren’t a new thing — they were an ongoing concern that many users saw as a threat to their game.

That TCGPlayer rolled out these new features in direct response to the latest buyout—one that generated unprecedented uproar in the Magic community—showed that they were aware of the shift in their users’ context, and were willing and prepared to react to it.

Finally, the story illustrates how making a better user experience can strengthen your brand.

TCGPlayer could have taken no action at all: after all, the buyouts had nothing to do with their product. Their product was simply the platform through which the buyouts were being executed.

However, TCGPlayer prides itself on being part of the Magic community. Their connection with players, collectors, and sellers is a core part of their brand identity.

Brands are built on action, not words. By recognizing their product had an opportunity to create a better experience for their users, and by acting on it, TCGPlayer took one of their core brand values and demonstrated its authenticity.

Consider how you can create a better user experience without fundamentally changing your product’s UI.

Pay attention to your user base. Be aware of their context, and consider how that context might change — and how that change could shape your product.

And consider how you can strengthen your brand by making a better experience.