With the rise of remote work in the midst of a pandemic, my working world is more accessible than ever before. But I find myself more dependent than ever on one of the most inaccessible forms of communication: the video call.

I’m deaf as a post. My hearing loss got worse throughout my childhood, which, as a side effect, helped me develop strong lip-reading skills. In practice, I can’t turn the sounds I hear into actual words that I can understand, so I rely on lip reading in conversations and meetings.

Early in my career, conversations took place over emails, instant messaging, or in person. These forms of communication worked well enough for my needs, and I was able to grow and thrive in my role.

I’ve been very fortunate over my career to work with companies with inclusive approaches to hiring and working. Some companies have been happy to hold remote interviews using instant text messaging or shift to in-person conversations. My teammates have defaulted to written communication and go out of their way to make sure our meeting environments include everyone. But these are situational adaptations for my specific needs and rely heavily on compassion and consideration from my team.

Over the last few months, workplace conversation and communication has shifted largely to some form of video calling. Even two years ago, this new reliance on video calls would have excluded me entirely from the working world and sidelined my growth and development. But the last couple of years brought exponential improvements in real-time speech-to-text.

Google Meet now has real-time captions. Other real-time speech-to-text tools like Otter are flourishing.

However, Google Meet’s approach to captions has a profound flaw: it’s designed to mimic captioning for movies and television — which has an insidious side effect that must be addressed.

Video calling isn’t great for anyone

The New York Times recently published an article titled “Why Zoom is Terrible,” which digs into the shortcomings inherent to video calling platforms that can leave us feeling “isolated, anxious, and disconnected.”

Among other issues (I strongly recommend reading the article), it singles out the issue of eye contact:

Video chats have also been shown to inhibit trust because we can’t look one another in the eye.

The original study behind this statement concludes that “… the use of systems that introduce spatial distortions negatively affect trust formation patterns.”

When captions are shown at the bottom of a window, the effect is magnified. While a viewer with typical hearing might be direct their gaze at their conversational partners (or themselves) around the middle of their screen, someone relying on the captions will be looking at the very bottom of the same screen.

This causes viewers to unconsciously perceive the person relying on captions as “uninterested, shifty, haughty, servile, or guilty.”

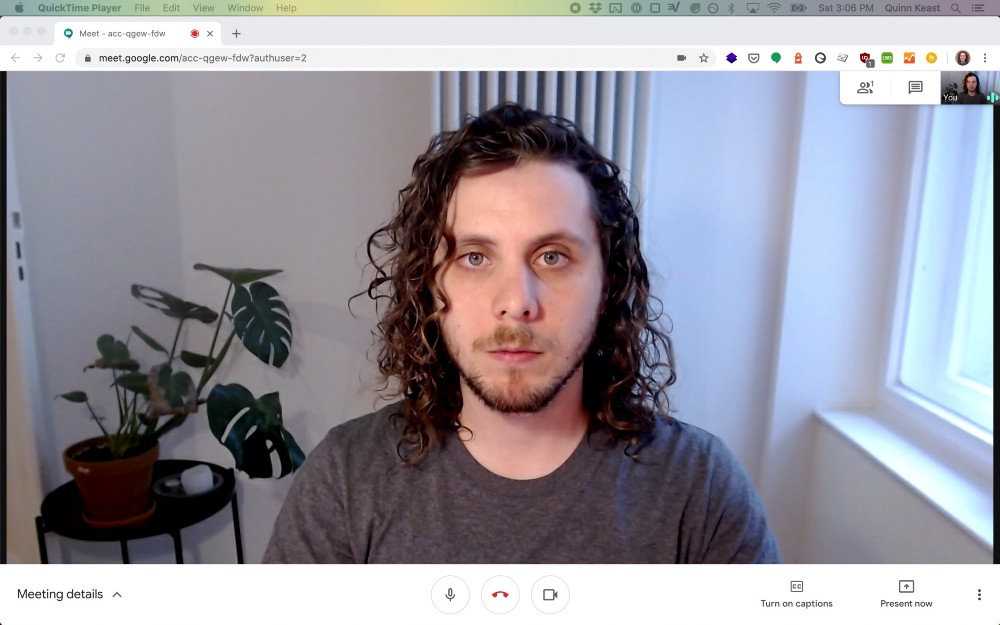

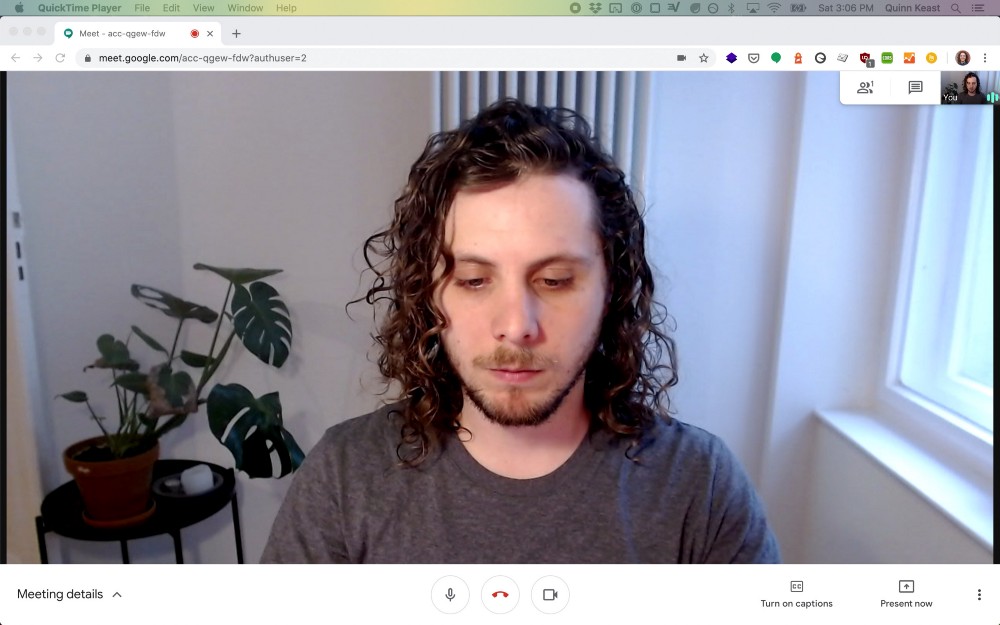

Compare these two screenshots: in the first, gaze is directed at the conversational partner, just above the middle of the screen. In the second, gaze is directed at the captions, at the bottom of the screen.

Which of these conversational partners appears active, engaged, competent, and trustworthy? The effect is magnified in large group conversations, where it’s easier to see the odd-person-out who doesn’t appear to be paying attention.

This is a bigger issue than a design problem: it’s also an ethical design challenge.

An ethical design challenge

On one side, real-time speech-to-text like Google Meet’s implementation makes these calls accessible to those living with hearing loss (and with inclusive design principles in mind, a wide range of others with situational or temporary needs).

On the other side, the current design implementation may be causing unintentional and permanent social and career damage for those same individuals.

A solution that actively harms those it purports to help, intentionally or otherwise, is not an inclusive or ethical solution.

What needs to be done

Short-term, I call on Google Meet to revisit their approach to captioning immediately. At the very least, the way Google implements captions in the platform should put those relying on them for inclusion on equal ground with their conversation partners.

Meanwhile, if your company defaults to video calls, I call on you to challenge “why.” I believe it would be better for companies to switch to any form of written communication before leaning on video calls.

Not only would this create a more inclusive environment for those living with hearing loss, but it would also create a more positive working environment for everyone by collectively shifting away from synchronous, reactive communication and towards asynchronous, considered communication. (Basecamp’s guide to internal communication is a model of inclusive communication foundations.)

While I have a hacked-together solution that is helping me address this issue, it’s hacky, unreliable, and expensive. Worst of all, it places my ability to belong into the hands of a private company that may not exist tomorrow.

That’s why, long-term, I believe we need system-wide, open-source, included-by-default solutions to real-time speech-to-text captioning. These solutions should be distinct from any specific application and designed from the bottom-up to deeply consider the human impact and side effects of the decisions we make in design.

We’re at a threshold where the technology exists to create a truly inclusive world for those living with hearing loss. Let’s do it together — and get the details right.

🔔 Update: These Are Design Principles for Real-Time Captions in Video Calls