I’ve been cycling a lot lately. Cycling’s got it all for people like me who like data and kit and bits and pieces: you’ve got your bike, you’ve got your computer, and it all orchestrates together to feed you a real-time stream of your speed, cadence, and power.

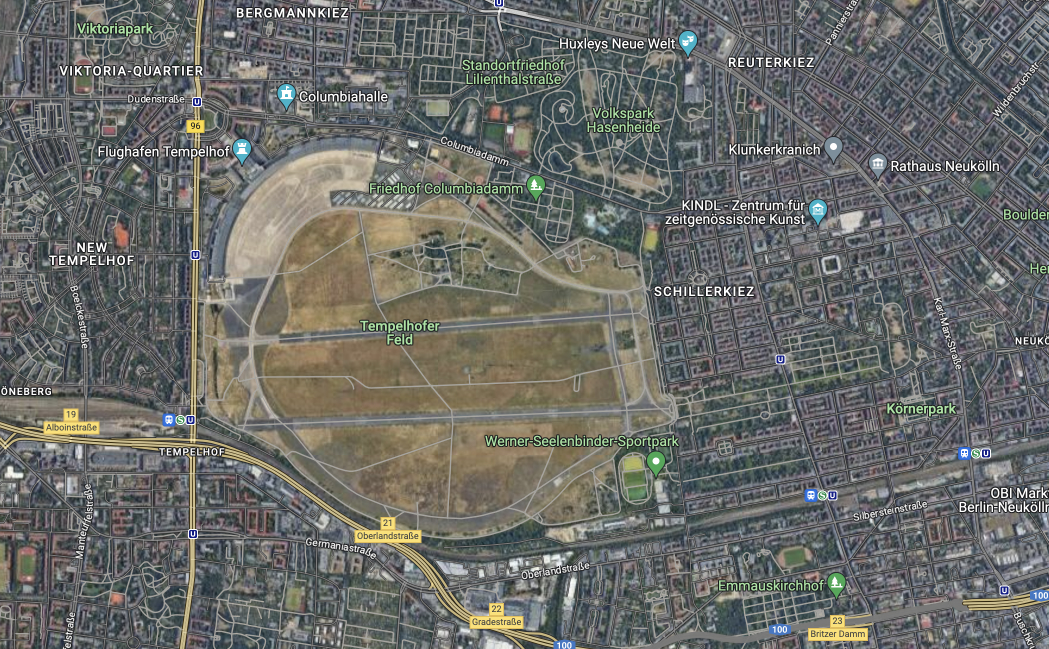

There’s a big field in southern Berlin called Tempelhofer Feld. It’s an old airport, abandoned after the fall of the Berlin wall, but the fields, runways, and curtains remain, reclaimed as a huge public space. It makes for a great cycling circuit: smooth tarmac for an almost 5km loop, and not a car in sight.

It’s also windy. It’s relentless.

Going in one direction, the wind at my back, it’s a blast. I watch my computer as I crank up to more than 45km/hour, nailing the cadence, and can’t resist dropping another gear to push my power ever higher. I’m within a gasp of 50km/hour with nothing but the lycra on my back.

Then I turn the corner and into the wind. Even though I’m exerting the exact same amount of effort, as measured by my power, my speed plummets. I’m lucky to hit 20km/hour.

It has an immediate psychological impact. With the wind at my back, I could see and feel the result of my effort. My speed, the feeling of the world whipping by, feeds into my energy, making it easier to keep pushing myself hard. But cycling into the wind, putting out the exact same effort, it becomes harder and harder to maintain my output.

I feel so slow.

It’s a feedback loop. The faster I felt, the easier it felt to keep pushing. The slower I felt, the harder it was to stay motivated.

I feel this same principle in my work, too. When I can see and feel the results of my effort, it’s easier to dig in. It’s easier to keep pushing. That’s the wind at my back.

But when the results of the work isn’t as visible or immediate, it can feel frustrating. This often happens when tackling more complex problems that take a lot of time and effort to solve. It can feel like pedaling into the wind—we’re putting in the same amount of energy but don’t feel like we’re getting anywhere. And that makes it harder and harder to keep going.

Knowing that this feedback loop exists, one approach is to create conditions for visible momentum and outcomes from the work we’re doing. For designers and product teams, this might mean setting shorter-term goals, looking for Minimum Lovable Product iterations, and focusing on rapid learning. All these things create that sense of forward motion and the positive feedback cycle.

It’s not always practical or possible for everything to be visibly awesome. Some things are Hard Problems. Some things take time and hard work without much visible progress until the critical breakthrough. This takes discipline. Putting in the effort, even when it doesn’t feel like it’s paying off.

But a cyclist who only rides into the wind can’t push through on discipline alone. They need a vision—something to aim for. It might be the triathlon they’re training for, or the promise of the Biergarten at the end of the ride. The same goes for our work: we need a clear vision of what we’re working towards and how this stretch against the wind is going to get us there.

And then there’s the team. In cycling, just as in work, riding into the wind is a different experience when you’re riding in a group. Grinding into the wind together (and griping about it after) can give back motivation the wind saps away.

This vision, the team around you, your own discipline, and those wonderful moments when you turn the corner and the wind’s at your back, are what get us through.

(Don’t forget the crosswinds. No matter how hard you push when cycling into the wind, crosswinds blowing wildly from unexpected directions are dangerous. For a cyclist, it can mean a crash, or at the very least, cutting the ride short. But in your work, it can lead to burnout or looking for new opportunities.)