This is part one of a two-part essay on creative AIs: in part one, my optimism and excitement for our creative future, and in part two, my discomfort with the prospect of living in a persistent unreality.

DALL•E 2 is wicked awesome.

For those with too many other things going on to follow the latest in AI, DALL•E 2 is the latest iteration of an artificial intelligence program that can create visual images based on prompts written in natural language. DALL•E 2 was preceded by (and uses) GPT-3, a machine learning model that generates human-like text.

I got early access to DALL•E 2 a couple of weeks ago, and I’ve been experimenting with all kinds of wild prompts and combinations. I’ve really tried to push the boundaries for what an AI could conceptually generate, and it’s mindboggling how far it can go with increasingly absurd prompts.

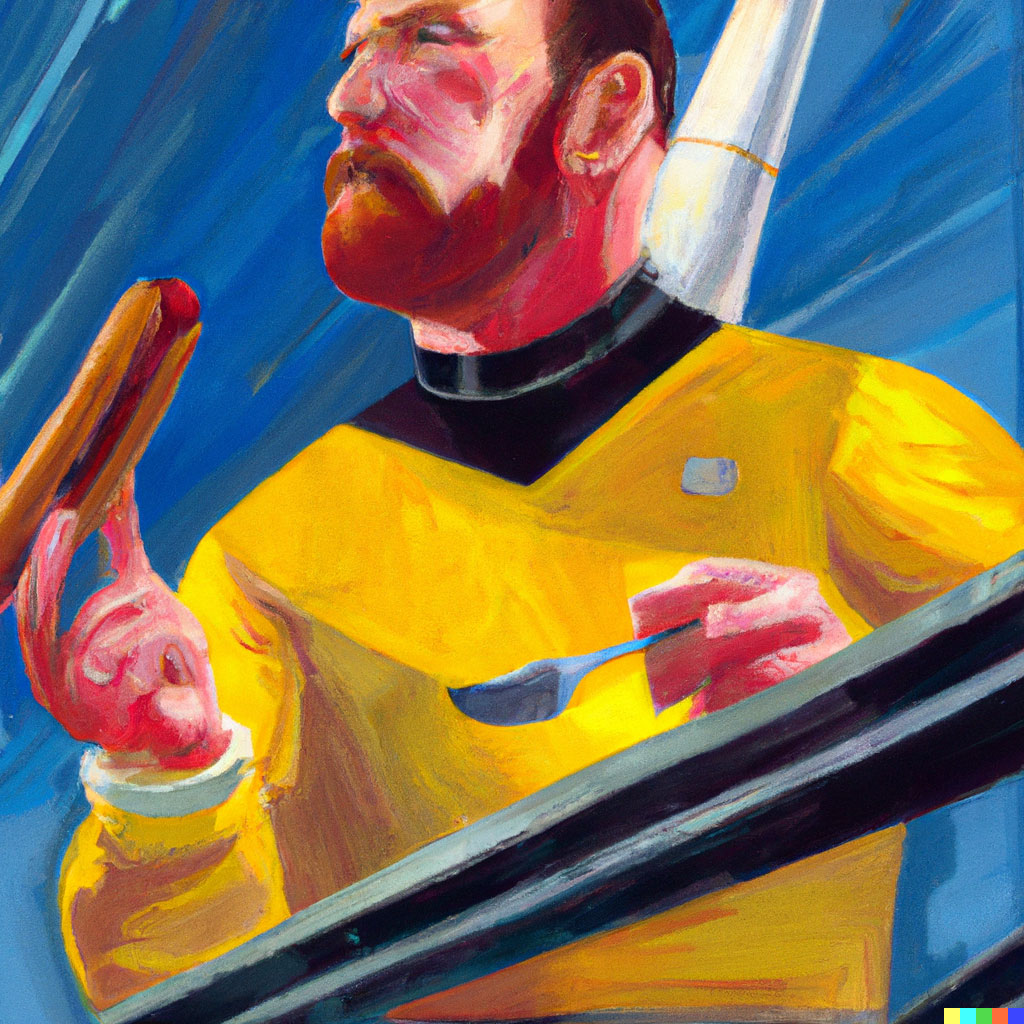

How about: “A gouache painting at a dramatic angle of William T. Riker in his Star Trek uniform eating a hot dog in a hot dog eating contest on the bridge of the Starship Enterprise”?

Or take that a step further: “A painting in the style of Todd McFarlane with a dramatic angle of William T. Riker with the goatee, wearing his red Star Trek uniform, eating a hot dog in a hot dog eating contest while standing proudly on the bridge of the Starship Enterprise.”.

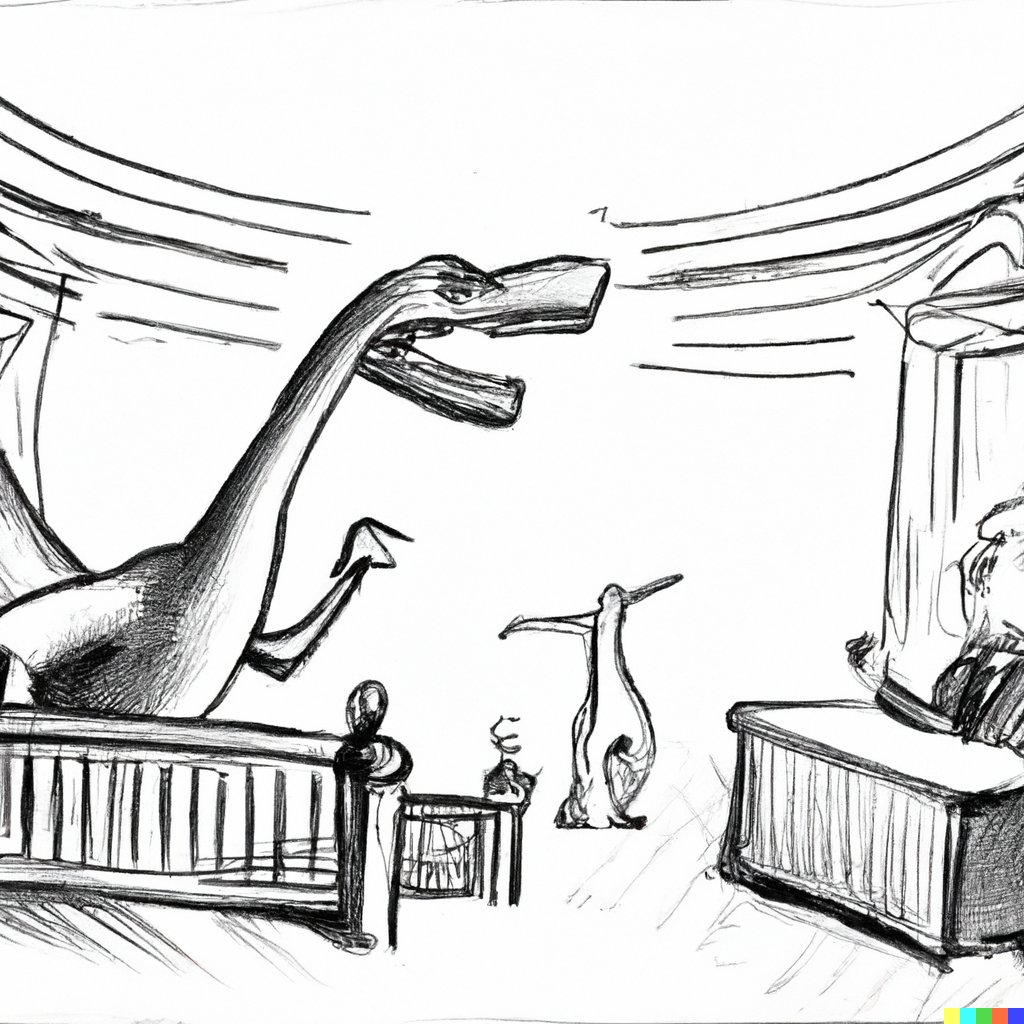

In a totally different direction, what about: “A 5-minute life drawing of an absolutely enormous brontosaurus rampaging through Kreuzberg”?

Or to follow up on the tale, “A courtroom drawing of an angry neighbour in court accusing an enourmous brontosaurus of rampaging”.

The part of me that bought an old Apple SE in a garage sale when I was eight years old, and taught myself how to make games with 3D Gamestudio when I was ten, is over the moon with how cool this is. It’s beyond anything I could conceptualize as possible even just a few years ago.

There’s another part of me—the designer in me—that’s uncomfortable with how DALL•E 2, GPT-3, and other future AIs will impact creative fields.

The more I explore these concerns, the more I’m convinced that we won’t feel much immediate impact. Few artists and illustrators and their ilk need to worry about being replaced by AIs. Instead, AIs will have the greatest impact in the long term, in how it influences the creative talent pipeline and what we value in art and media.

My education was in graphic design. On my first day of school, I really, really sucked.

Most things we do when we’re learning to do something for the first time really suck. Like all learners, most of my time spent learning to be a graphic designer was spent practicing and failing and learning from those failures, until, by the time I left school and started working as A Designer, I was able to do work that was largely good enough.

I’ve spent every year since continuously learning and refining and redefining my craft, from graphic design to product and UX design, doing it again and again until I could consistently do work beyond good enough.

And yet, for the vast majority of creative outcomes, all that’s actually needed is good enough. Most things don’t need outstanding design. Most things need design that’s good enough for what and who it’s for.

That’s great news for folks getting started in creative fields like me way back then, because the baseline for good enough is pretty low. You don’t need to study for a decade to reach good enough. A few years of consistent practice and repetition and feedback will get you there.

In fact, digital tools already accelerated how quickly creative learners can get repetitions in: a graphic design student learning their craft on a computer rather than with expensive gouache on expensive paper can iterate and experiment and make mistakes that help refine their skills faster. Given the same length of time spent learning a craft, the creative learner’s skill will be better than before. In effect, digital tools established a higher baseline for good enough. What’s considered good enough today is already way better than what was good enough when I entered the industry 13 years ago.

For many creative objectives, given a precise prompt and human curation, DALL•E 2 is capable of creating subjectively better outcomes, much, much faster than any human—not only good enough, but better than good enough.

While today’s baseline for good enough was established by learners having new tools at their disposal, AIs like DALL•E 2 establish a new baseline for good enough in themselves, rather than as in as a tool in the service of human learners.

I think this is going to create an immediate shift in digital channels, publishing, and graphic design: where previously free or low-cost stock photography and illustration would have been used in these good enough applications, Dall•E 2 and other AIs are capable of churning out just-as-good-and-better-yet outcomes.

At the same time, I don’t think this is going to have any real significant impact on creatives today. The reality is multifold: first, those who use free or low-stock cost themselves today either can’t afford to or aren’t willing to pay for an actual creative specialist for what they’re doing. And those that use free or low-cost stock within product work, like agencies with low project budgets, won’t change much about what they’re doing because one source of free or low-cost imagery is replaced with another that just so happens to be created by an AI.

Those who pay for brilliant creative work will continue to do so—because they know that good enough, isn’t.

Brands depend on consistency and alignment with their brand identity and values. These brands need the thoughtfulness and deliberate curation provided by a real human doing work to brief. For great creatives, nothing is going to change.

Instead, the real challenge we’re going to face is in the longer term: in how a new baseline for good enough is going to impact the pipeline for creative talent.

And I’m betting this is going to lead to a whole lot of folks dropping out of, or avoiding creative fields altogether as a career path.

A new baseline for good enough means that anyone considering a creative career will have to become better to succeed in their career than they would have had to become before. And that means it’ll take longer and take more work to just reach the level of good enough for someone to land their first role in the creative industry and compete for work.

This will be a trailing indicator. Ten years from now, I worry we’ll be closer to being an industry of seniors, less able to be disrupted by new ideas and perspectives.

But despite this, I think that Dall•E 2 and its ilk will spark a new wave of human creativity. AI will become another tool in our creative kits that we wield to our own purposes. And when AIs take over the role of producing the chaff that’s good enough for most applications, humans will instead find new ways to be creative in spaces and ways where no AI can reach.

I think we’ll see a rise in physical, tactile mediums in art. We’ll assign more value to tangible, original works, over one-off digital mediums and reproductions. We’ll admire bodies of work, like graphic novels, that capture a visual aesthetic and opinion and carry it out over space and time. Perhaps we’ll also see a vibe shift in art styles towards those that AIs are less capable of doing well—like graphic design heavy on typography and rhetoric. Perhaps this shift on its own will be enough to counter any disruption to the pipeline of creative talent.

After all, Dall•E 2 and other creative AIs represent a new constraint for creatives—and constraints beget creativity.