I’ve been working on designing Ditto’s AI content system for the last few months (among a huge pile of other things that made up Ditto 2.0).

I’m a huge fan of product style guides. I think the words we use in products have a wildly outsized ROI compared to almost everything else in design, because every word packs in a crazy amount of symbolic meaning. Years ago, I launched the Product Language Framework, a set of UX copywriting and style guidelines that can be used as-is for everyday reference, or teams can clone it and use it as the basis for creating and deploying their own style guide.

The moment ChatGPT 3.0 hit, I wondered if a LLM could be used to automatically lint your product copy against your style guide. I tried it out and it seemed promising, but annoying. Component libraries and design tokens are deeply integrated into the designer and developer tool stack, so they “just work” as part of the regular workflow. Anything to do with a LLM seemed like a bunch of extra steps that would be hard to pull off in a way that people would actually use in their workflows.

I joined Ditto last year because they were thinking very deeply about how to systemize product copy along with everything else we’ve systemized in the course of building products. I had an inkling that this was the kind of platform we’d need to get style guides integrated into the actual design and development workflows.

But we’ve been careful about how we approach AI at Ditto. The last thing we want to do is put blue food coloring in it. Even setting aside that we were deep into the biggest product overhaul we’d ever done, we wanted to make sure we were intentional about providing real, meaningful value with any AI features.

The right moment came not long after Figma Config, where we soft launched Ditto 2.0 and talked with a lot of curious teams. We built and shipped Ditto’s AI content system in a matter of weeks. On the design side, we ran into some interesting challenges I thought I’d share.

First, a bit of conceptual underpinning. Ditto’s AI content system is a mix of:

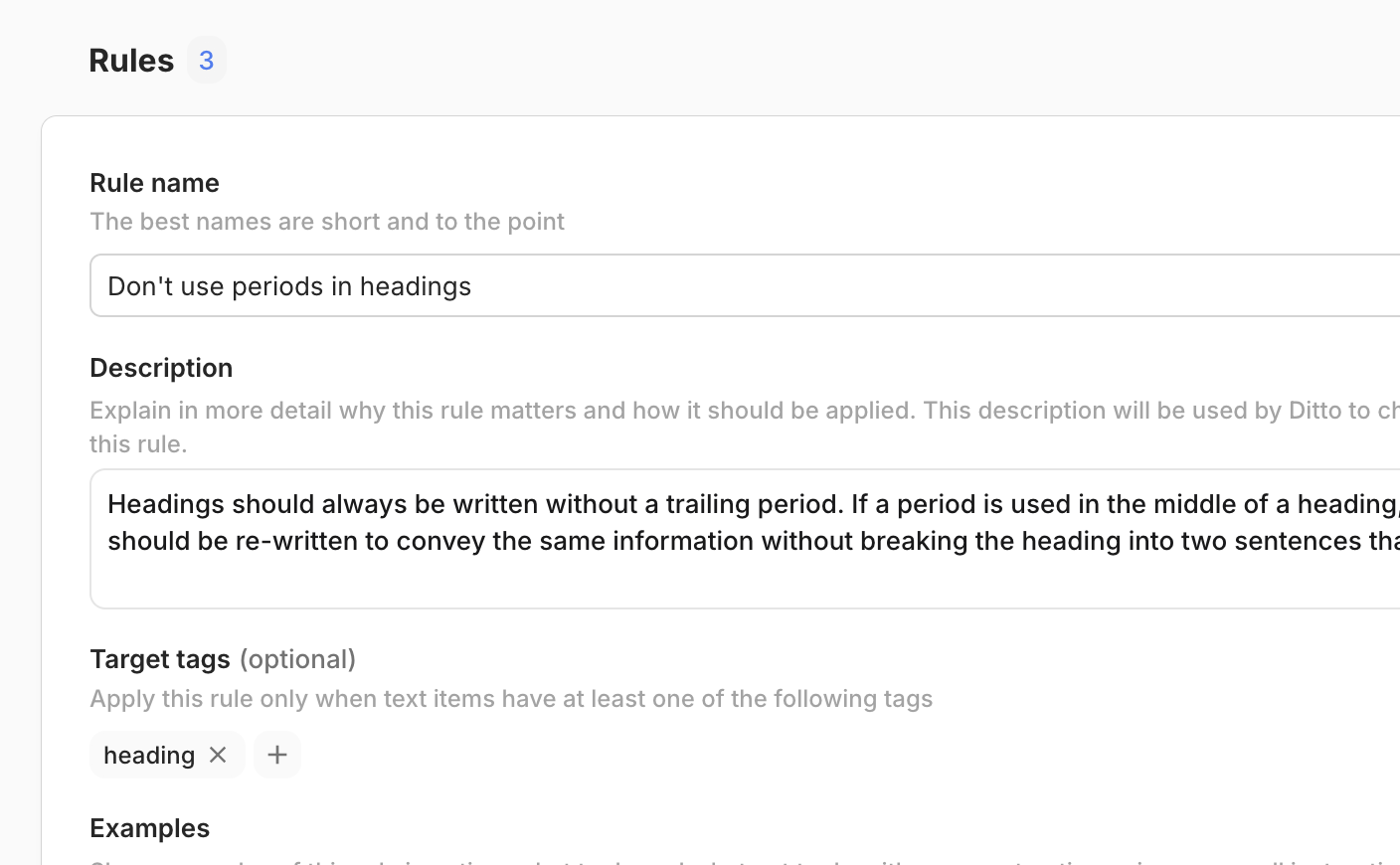

Style guides. These are made up of rules, with a name, description, and set of examples. A team can have multiple separate style guides, managed through the Ditto web app, and each style guide can be represented in JSON.

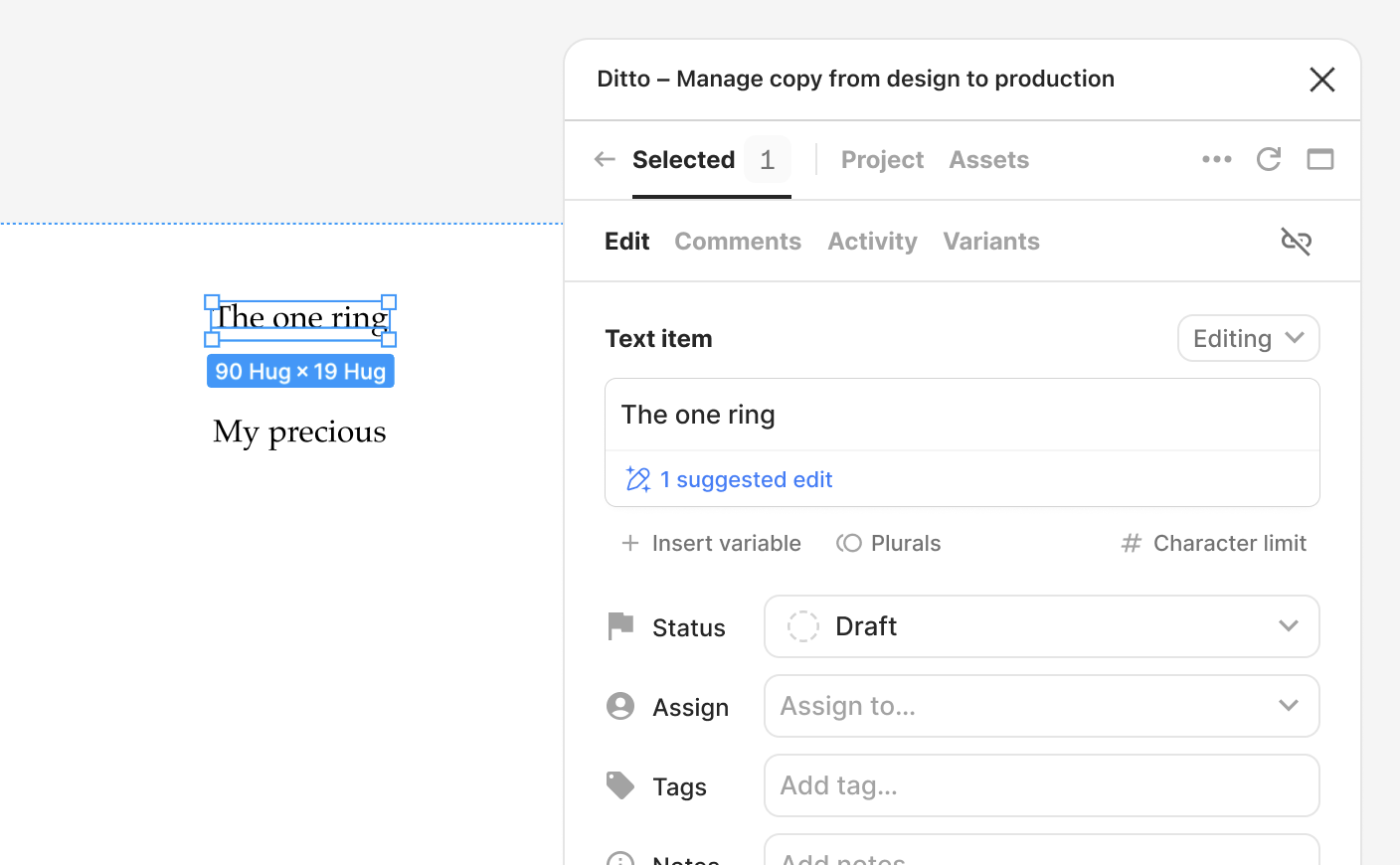

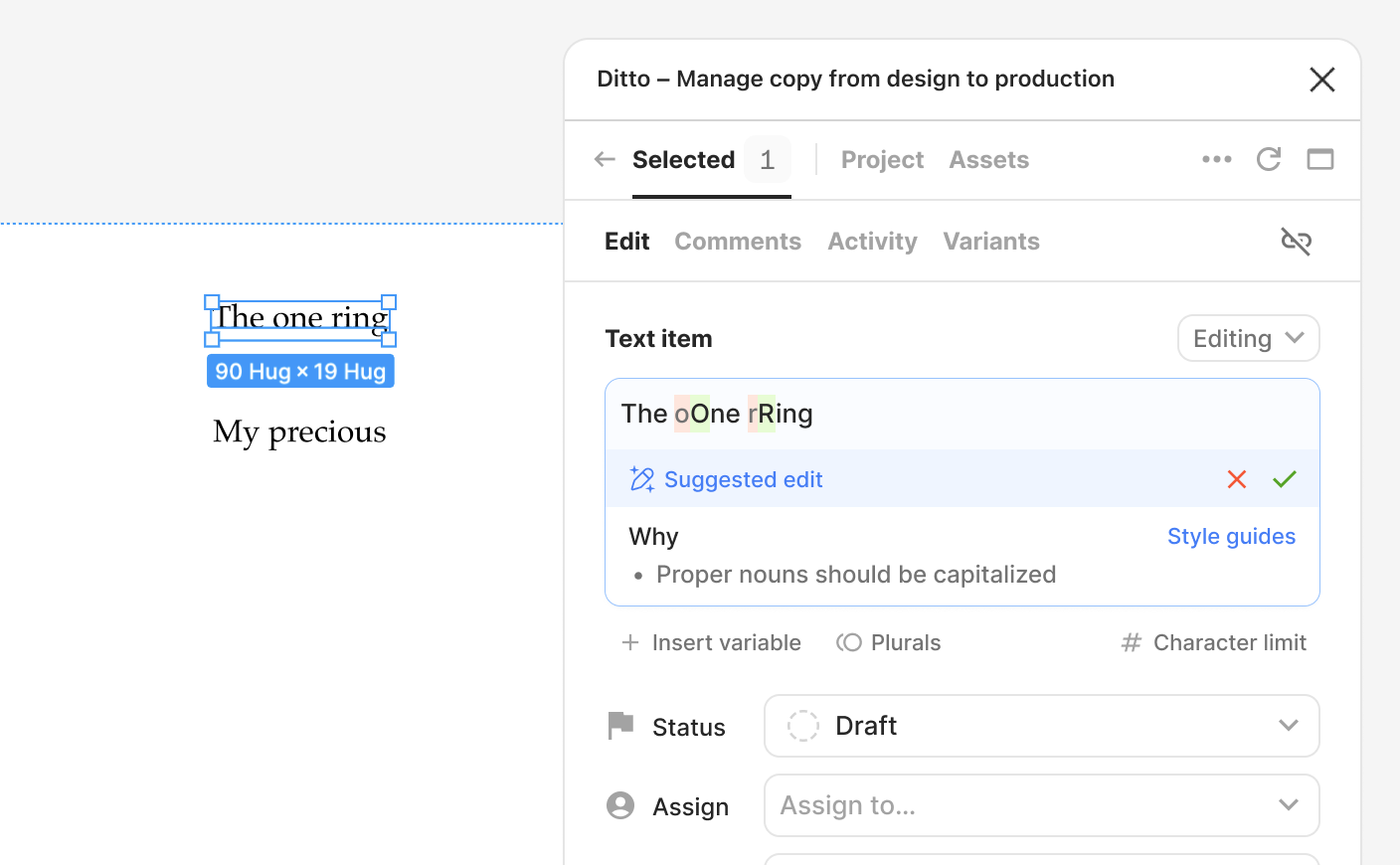

Magic edit. Any time a text layer is selected in Figma or in the Ditto web app, we “lint” the text against the style guides using a LLM. If there’s anything about the text that breaks a rule in the style guide, we generate a suggested edit that’s in itself aligned to the style guide, and explain why in a way that ties back to the source rule.

Magic draft. Any time a text layer is selected in Figma or in the Ditto web app, the user can trigger magic draft to help write what I’ve been calling “the draft and a half.” Ditto will take the context of the existing text, other text in the design, any additional metadata captured by Ditto’s platform, and generate a suggestion that combines the user’s input together with that context and the style guide.

With those concepts in place, here’s some things we learned.

Style guide rules are hard

We researched dozens of style guides and found a huge range in the types of rules that they contained.

For example, my own Product Language Framework has:

- General rules of thumb, like “use conversational writing”

- Style and mechanics, like “use this region’s date format” or “use en dashes between ranges”

- UI-element-specific guidelines, like “button labels should follow the formula verb + noun”

- Word lists

Many of these rules contradict each other depending on context, and other rules have edge cases that that contradict themselves. Consider: one should use active voice rather than passive voice. Unless, of course, one aims to avoid assigning responsibility for an action.

Our rule system and way of handling examples needed to support all of these rules and examples intuitively, and integrate well with our use of LLMs—remembering that every rule would be part of the same context.

As a bonus problem, we needed to design a default style guide available to all workspaces, which would let everyone encounter the potential value of the AI content system—meaning it had to reliably catch occasional issues that most product content will have, but not too many issues.

Style guides for AI content systems are not style guides for human consumption

Most style guides that act as standalone artifacts for reference are formatted and organized for human consumption. Someone goes about content design for them. My own Product Language Framework tries to be easy to consume with structure and categories and nested rules. The first version of our guidelines needed to be more minimalistic, because we needed folks to focus on creating good rules rather than designing content for human consumption.

LLMs really, truly, want to do shit in their own way

We knew going in that the non-deterministic nature of a LLM could be a challenge. Some of our earliest tests gave us confidence that it was feasible, but the more we experimented, the more trouble we ran into. It turns out that it’s very, very hard to align LLMs to the task of checking short product copy against style guides without injecting their own “opinions.”

This makes sense because most content that LLMs are trained on is not written against your style guide, but rather a huge corpus of text that follows other style guides or no style guide at all. Getting a LLM to follow your specific style guide is somewhat asking it to work against its own probabilities.

But we were really surprised by what things ended up being most challenging.

Here’s some examples of the kinds of suggestions we were getting all over the place:

Most of all, it’s total hell to make an LLM correctly use typographic quotes instead of dumb quotes. This is a totally valid use case for automated style guides that’s almost impossible to pull off manually, but would be a perfect detail for an AI content system to handle.

It just found so many ways to ignore it, work around it, and in one memorable case when we turned ourselves inside-out trying to prevent this in the prompt, it wheedled around it by changing a rule to the literal opposite of the actual rule and pretended it was real.

That leads me directly into…

False positives (a suggestion that isn’t useful or is wrong) are way worse in aggregate than false negatives (a missed suggestion)

This at first felt counterintuitive, but the more we tested, the more we discovered that it was more important to avoid triggering unhelpful suggestions than it was to avoid missing a broken rule.

The thing about product copy is there’s a lot of it. Every string in your product is a piece of copy. Every time you select a text layer in Figma or in the web app, we lint it. And if even 10% of those trigger a false positive, then in no time at all, users lose trust and develop “banner blindness” to it, and won’t notice at all when there’s a real, legitimate catch.

The risk of a missed suggestion is near nil.

Prompt engineering is hilarious

Two separate people described our prompting solutions as:

“You sound like you’re giving instructions to a small child.”

We had to solve a lot of problems related to the LLMs wanting to do their own shit by exploring wildly creative prompts and multiple judgement systems. My colleague Reed Barnes shared some some things we learned about around building on top of an LLM from the engineering perspective.

It’s hard to be both valuable and unintrusive

So, so many products have just crammed AI features in wherever they fit to ride the AI hype wave. Based on what I’ve seen of the sales process these days, this isn’t surprising.

But with Ditto we wanted to be very thoughtful around the fine line between “useful value surfaced proactively” and “annoying, untrustworthy crap that’s just another example of a product cramming AI into everything.”

This was both a UI design challenge and systems challenge. Ultimately it came down to testing. Testing for this kind of product space is inherently subjective and iterative. Somewhere along the lines a human has to observe and evaluate the suggestions and decide if they’re actually good suggestions, and then figure out what to do about that.

The feedback loop needed for “drafting and iterating on product copy” is dramatically different from “testing and iterating on the product that helps to draft and iterate on product copy.” We needed to be able to test both quality (good suggestions for real issues) and reliability (consistently good suggestions for real issues).

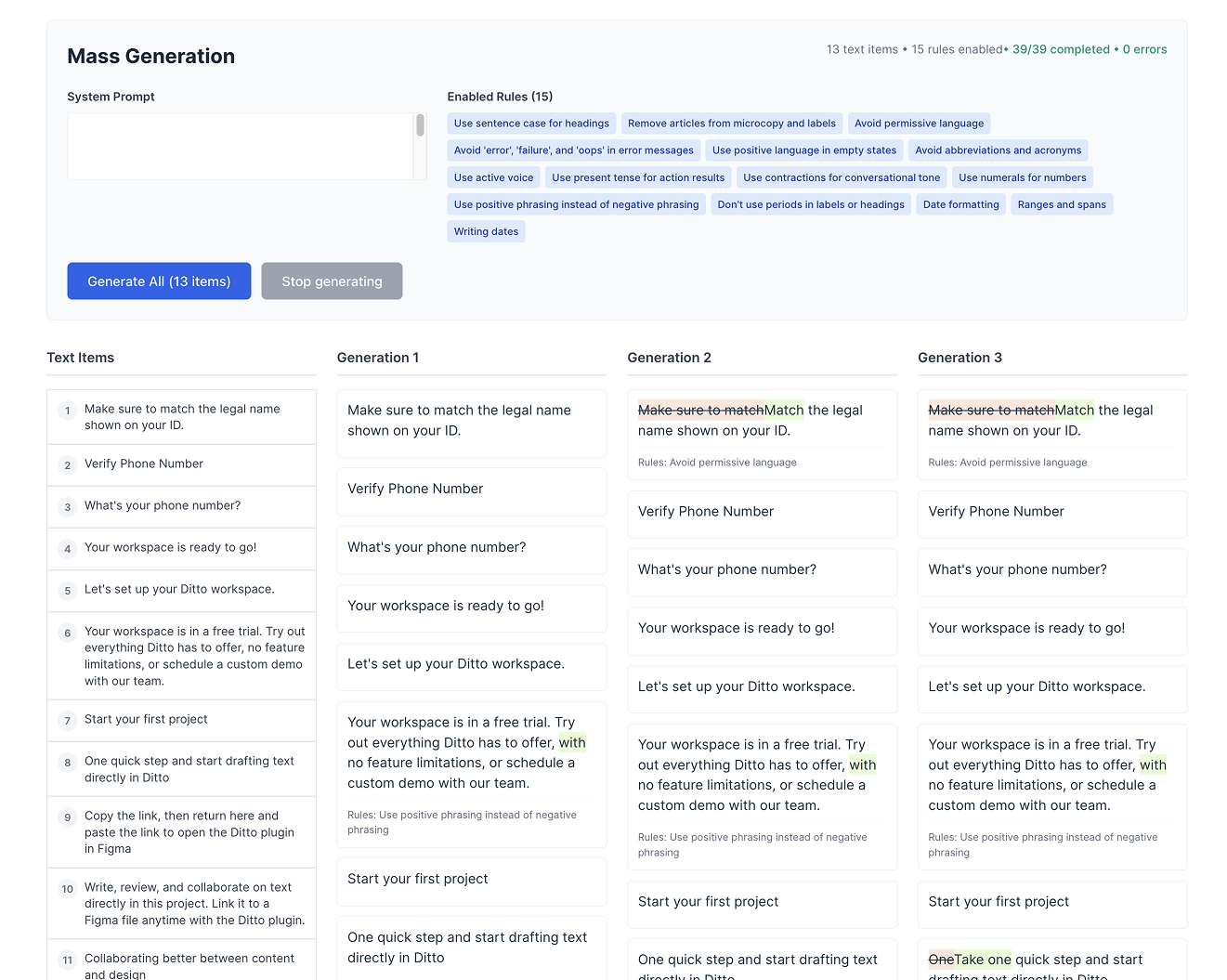

We ended up building a cool internal tool to test and iterate on our rules and the LLM integration at scale. We’d make a tweak, then run the linting against dozens of known strings, repeatedly, and then we could visually identify themes and decide what to do about it.

Making an LLM-powered tool for AI style guides is way harder than it seems, but now that it’s actually working, it feels like a totally normal extension of the designer/writer/developer toolkit. I’m looking forward to seeing what we learn as we ship the rest of it with magic draft.